Article 2(e) of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide declares that “forcible child transfer committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such amounts to genocide.”

Article 2(e) of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide declares that “forcible child transfer committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such amounts to genocide.”

Thus, forcible child transfer is one of the genocidal acts listed in Article 2 of the Genocide Convention. The act prohibits transferring children of the group to another group with intent to destroy national, religious, racial and ethnic groups in whole or in part. The arguments for including the forcible child transfer in the Genocide Convention were twofold. First, is the vulnerability of children, their “dependence, futurity, and malleability” and, second, the destructive consequences of this practice for the viability of the group.

Forcible child transfer operates in the borderline of cultural and biological genocides, and is unique in its application as constructs a new child identity through the destruction of the former. In line with the mission of the Genocide Convention which not only punishes the worst forms of violence, but also protects the human groups, forcible child transfer clause protects children as a nucleus of group viability.

The Article 2(e) involves separating children of the protected group from their group and placing them under another group’s control. Article 2(e) offers no requirement of full integration of the transferred children into another group, so that being under the other group’s control is enough to record Article 2(e) violation. There is also no mention of duration in the Article and the preparatory materials of the Genocide Convention also did not impose any time restriction. So, related to the duration the approach would be the perpetrator’s intent - the children must be under the control of another group for “as long as the perpetrator intended the separation to destroy the group.” So, as a result the transferred children do not identify them with their group.

The consequences of forcible child transfer outweighs the motives such as “to benefit the affected children” or “to save” them or “treat them well.” Genocidal culpability is this case is assessed by intent to destroy a group. As this relates to the minimum duration, here again the perpetrator’s intent is the most decisive; children must be under the control of another group for “as long as the perpetrator intended the separation to destroy the group.”

Meanwhile, the term “forcibly” is not restricted to physical force, and may include any acts of threats, threats of force, inflicted trauma, or coercion such as that caused by fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression, or abuse of power, or by taking advantage of a coercive environment which would lead to the forcible transfer of children from one group to another group.

Forcible child transfer is recognized to be an old phenomenon with a lot of examples from the history.

Devshirme in the Ottoman Empire is mentioned as an example of forcible child transfer. By the words of the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople Zaven Der Yeghiaian, in this way the Ottomans were able to increase their race and this old blood tax phenomenon has culminated during the Armenian Genocide.

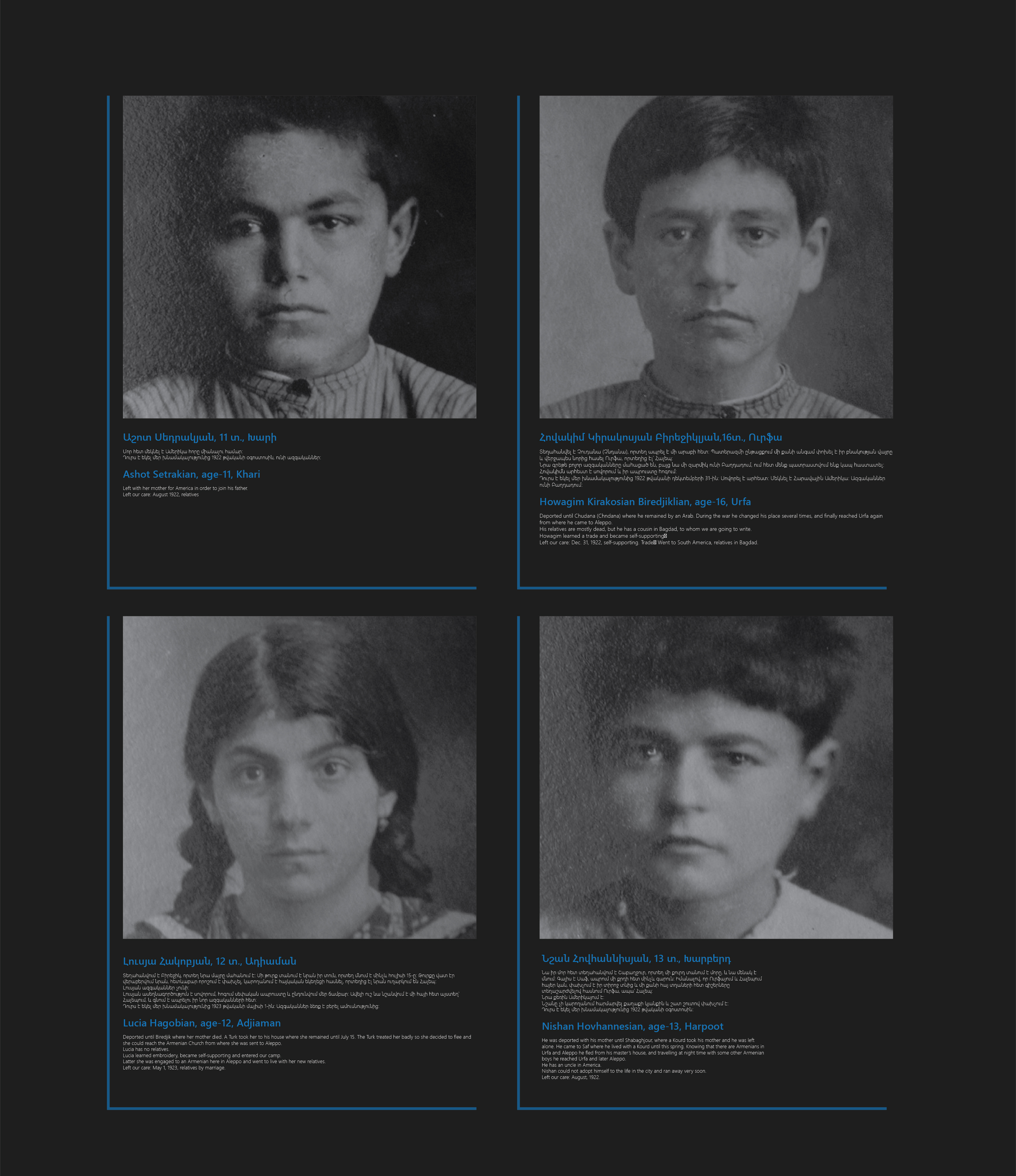

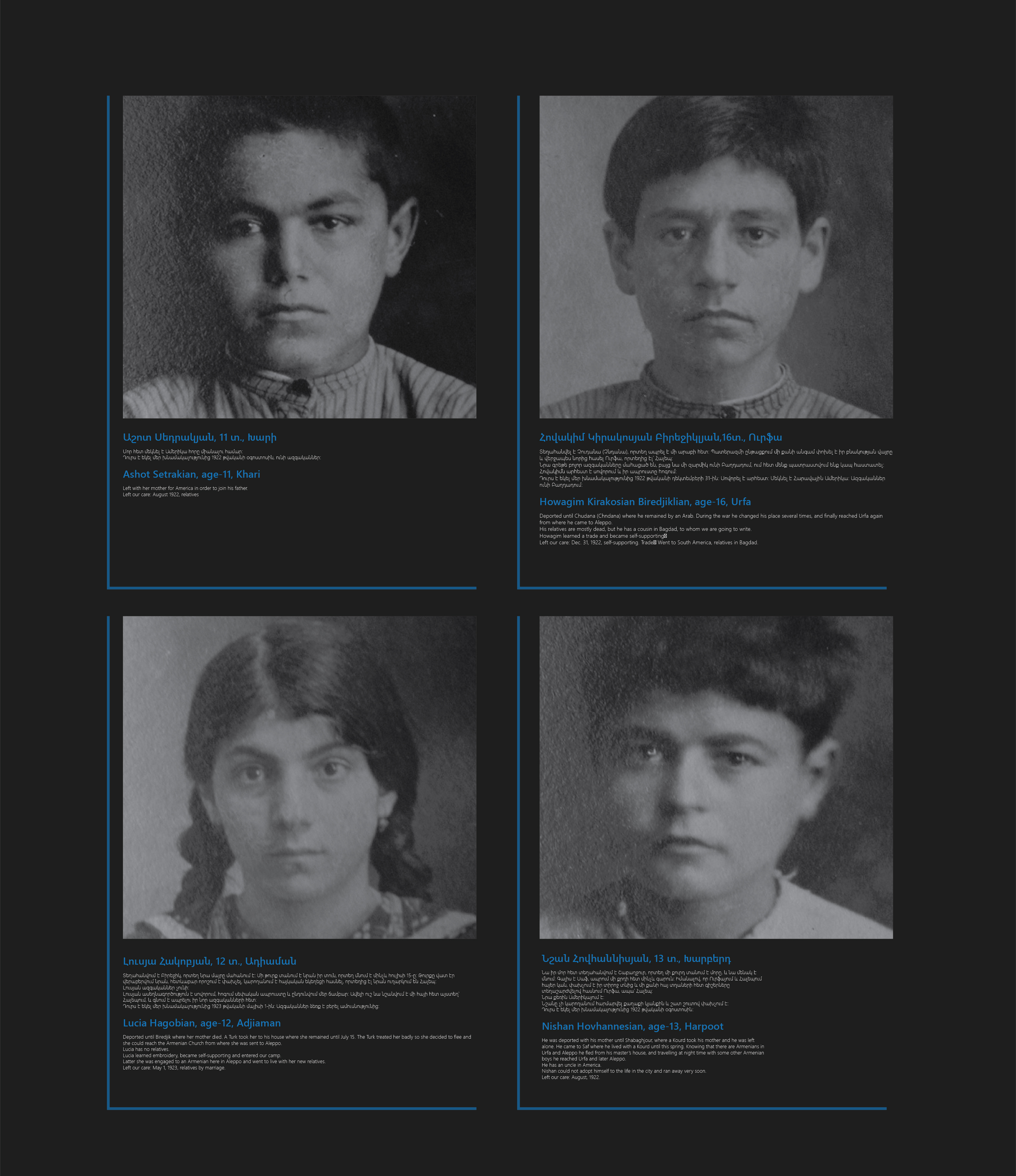

There have been many instances of children being forcibly transferred throughout history; but the Armenian Genocide is a classic example of genocidal forcible child transfer.

Other wide scale child removal programs were connected with acculturation and westernization or “education” of indigenous children. In the mid nineteenth century in Australia, Canada, and the United States indigenous children were transferred from their groups for education and westernization. During 1920-1970s, the Swiss removed Roma children for the same purpose. Starting from 1920s a policy of Russification of indigenous Siberian children was carried out: they were removed and placed in distant schools in the Soviet Union.

During WWII “racially valuable” children, mainly Polish, were forcibly removed from the occupied eastern lands to Germany for their Germanization. According to a well-designed plan

racially valuable children were “robbed or stolen,” were educated in special institutions, orphanages or in German families. This policy was extended to children up to 8 to 10 years of age as it was believed that a real ethnic transformation- germanization - is possible only up to this age. The children received German names and new birth certificates, without any connection to their relatives. During the hearings of the Nuremberg Military tribunals “the crime of kidnapping children” was even called to transcend “the crimes of mass killing of the Jews, the atrocities in concentration camps, the savage medical experiments, and many more ruthless forms of torture and extermination practiced by the Nazi fanatics.”

The forcible transfer of Armenian children was a structural component of Ottoman genocidal policy. The Ottoman Government legalized and encouraged the transfer of Armenian children.

Transfer and assimilation were pre-planned by the Young Turk Government, and implemented as soon as the deportations started in 1915. As early as the beginning of World War I the Turkish government started opening new orphanages with the long-term goal of receiving “parentless” Armenian children, developing an entire legal system to manage the process. Several government orders guided implementation on the ground. An order of June 26, 1915 mandated that Armenian children up to the age of ten

“be collected and placed in orphanages for education and upbringing.” A similar decree a month later openly stated that

“children likely to become parentless during the transportation of Armenians” were to be placed in government-run orphanages. Soon the policy was extended to cover boys up to twelve years old and girls up to fifteen.

Armenian children were distributed primarily among influential families, most often as unpaid servants, many subjected to inhumane treatment. A wartime organization affiliated with the Red Crescent Society and under the patronage of such leading figures as Mehmed Talaat, Ismail Enver, Halide Edib Adıvar, and other prominent men and women helped organize their distribution to Muslim homes. The Ministry of the Interior transferred hundreds of Armenian orphans from Anatolia to Istanbul for placement in

“selected Muslim households or employment in factories, workshops, farms, and businesses.” Girls were usually married to Muslims or subjected to sexual abuse. Armenians were sent to villages and towns where there were no other non-Muslims so that they could be

“educated and assimilated according to local customs.” Muslim families were encouraged to adopt Armenian children; the government not only subsidized them, but promised them their families’ property if it could be identified. The entire process was supervised by the central government.

In the orphanages Armenian children were raised and educated with Turkish, Arab, and Kurdish orphans. The government forged birth certificates that replaced birth names with Turkish ones. The children were required to speak Turkish and to disown whatever they remembered of their past lives. They were raised according to Islam and Turkish customs.

Surrounded by the population that had killed their relatives, assured that there were no Armenians left, and living under latent threat, Armenian children had no choice but to adapt. The youngest easily forgot, but the older ones were afraid to express their thoughts, quite conscious of what was actually happening. Nearly 200,000 children underwent such experiences.

The intent of this practice was a full eradication of every Armenian element in the transferred children, thus constructing a new identity of a Turk on a biological, ethnic and historic Armenian origin.

Edita Gzoyan, Doctor of History

AGMI Deputy Scientific Director

1. International Military Tribunal, Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control; Council Law no. 10, Nuremberg, October 1946 -April 1949, Vol. 4 (Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1949.

1. International Military Tribunal, Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control; Council Law no. 10, Nuremberg, October 1946 -April 1949, Vol. 4 (Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1949.

2. Kurt Mundorff, “Other Peoples’ Children: A Textual and Contextual Interpretation of the Genocide Convention, Article 2(e),” Harvard International Law Journal 50, no. 1 (2009): 61-127.

3. Ruth Amir, Twentieth Century Forcible Child Transfers. Probing the Boundaries of the Genocide Convention (London: Lexington Books, 2019).

4. International Military Tribunal, Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control; Council Law no. 10, Nuremberg, October 1946 -April 1949, Vol. 4 (Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1949).

5. League of Nations Archives, Classement 12, Document 9640, Dossier 4631, Letter of Zaven Patriarch, 1 November 1920, Constantinople.

6. Matthias Bjørnlund, “A Fate Worse than Dying’: Sexual Violence during the Armenian Genocide,” in Herzog D. (eds) Brutality and Desire. Genders and Sexualities in History (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

7. Նարինե Մարգարյան, «Հայ երեխաների թրքացման գործընթացը Օսմանյան կայսրության պետական որբանոցներում (1915-1918)», Ցեղասպանագիտական հանդես 4 (1), (2016), 25 – 43.

8. Uğur Ümit Üngör, “Orphans, Converts and Prostitutes: Social Consequences of War and Persecution in the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1923,” War in History 19, no. 2 (2012):

9. Taner Akçam, The Young Turk’s Crime against Humanity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

10. Nazan Maksudyan, Orphans and Destitute Children in the Late Ottoman Empire (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014).

11. Nazan Maksudyan,“Foster-daughter or servant, charity or abuse: Beslemes in the Late Ottoman Empire,” Journal of Historical Sociology 21, no. 4 (2008): 488–512.

12. Vahakn N. Dadrian, “Children as Victims of Genocide: The Armenian Case,” Journal of Genocide Research 5, no.3 (2003): 421-437.

13. Ara Sarafian, “The Absorption of Armenian Women and Children into Muslim Households as a Structural Component of the Armenian Genocide,” in In God’s Name: Genocide and Religion in the Twentieth Century, ed. Omer Bartov and Phyllis Mack (New York: Berghahn Books, 2001).

14. Keith David Watenpaugh, “Are There Any Children for Sale?,”: Genocide and the Transfer of Armenian Children (1915–1922),” Journal of Human Rights 12, no. 3 (2013): 296–308.

15. Ցեղասպանություն հանցագործության կանխարգելման և դրա համար պատժի մասին կոնվենցիա/ http://ոww.Un.Am/Res/Un%20treaties/Iii_1.Pdf