Bodil Katharine Biørn

Bodil Katharine Biørn was born in 27 January 1871, in Kragerø, Norway. She has studied music in Germany and got religious education in Oslo. After working for ten years as a nurse in Norway and Germany, she has joined the Norwegian branch of

“Women Missionary Workers” organization (1).

In winter 1905, Bodil was sent to the German Hospital in Marash, founded by the German Eastern Mission. Shortly afterwards, she was sent to Mezre to work in a German orphanage. There was a missionary station in Mezre, but Mush had only two Turkish doctors, one of whom was a military doctor. In 1907, Biørn settles in Mush, where she stays for nine years. Here she established an outpatient clinic, which served up to 4,000 visitors a year (2).

Throughout her stay in Mush, she continued to make home visits to villages in the region, providing medical care to Christians and Muslims alike. Bodil begins to teach medicine, to have assistants and substitutes in case of need. Biørn establishes a school for illiterate women, where the orphanage girls start teaching them reading and writing. For fundraising purposes Biørn had brought with her a camera from Norway to present the life of the locals in the branches of WMW. Her photos were used in reports at Women Missionary Workers’ meetings, and later served as evidence of the genocide (3). In 1910, Swedish missionary Alma Johansson joined Biørn. Bodil was already known in the region by the nickname “Doctor”, so Johansson was called “the new doctor”, which Bodil considered both “oppressive” and “binding” at the same time (4). As of 1913, their missionary station was consisted of male and female orphanages and male school, and by 1914, they had already turned the outpatient clinic into hospital.

In 1915, Biørn felt the full weight of the brutality of the Armenian Genocide carried out by the Turkish government. On July 1915, with the promise that they would be taken to Mesopotamia, the students raised by Bodil and Johansson were taken out of the city by the Turkish police and burned-alive (5). This incident was a huge psychological crash for both women, but there was no time to mourn. Turning back wounded Turkish and Armenian soldiers brought to Mush typhoid epidemic which was spread in the front. As there was no special hospital for them, the infection soon spread throughout Mush. Johansson and Bodil focus their efforts to treat infected people. According to Bodil, the condition of the Armenian soldiers, who were exhausted as a result of serving in the labor battalions, was especially difficult;

“many have died, some survived to be killed later” (6):

War-related censorship prevented missionaries from presenting the situation in the Ottoman Empire to the world. Bodil’s first letter to WMW dates back to September 1915. There she presents the fire of Mush in very disguised words, and asks permission to take some Armenian teachers with her to Norway, without revealing the reason (7). Many times her letters were just biblical psalms, through which she tried to convey her mental state to her colleagues, for example:

“I sink in the miry depths, where there is no foothold. I have come into the deep waters; the floods engulf me. I am worn out calling for help; my throat is parched. My eyes fail, looking for my God. Those who hate me without reason outnumber the hairs of my head; many are my enemies without cause, those who seek to destroy me. I am forced to restore what I did not steal. (Psalm 69: 2-4)” (8). Along with some Armenians rescued from Mush, Johansson and Bodil go to Mezre and work for some time with Maria Jacobson and Karen Marie Peterson, after which Johansson travels to Constantinople to present a report on the events, whereas Bodil turns back in hope to Mush to find possible survivors, including some of her students. There she gathers the Armenians left in hiding, and presents them all as Protestants, manages to provide them with food and medicine (9).

In February 1916, due to the advance of the Russian army, the Turkish authorities again force Biørn to leave. She arrives in Bitlis with some Armenians, where another catastrophe awaits her:

“They took away my last Armenian friends and the children I had saved” (10). Bodil then travels to Diyarbakir with a Turkish policeman who accompanies her, where she tries in vain to turn them back for three weeks, then to Aleppo, and from there to Haruniye; Cilicia, where she works as a nurse in a German orphanage for about a year. In 1917, Bodil moves back to Norway with an Armenian boy she adopted in 1915, whom he names Fridtjof-Raphael in honor of the great philanthropist Fridtjof Nansen.

After World War I, Biørn returned to the Ottoman Empire for field work; and from there she left for the Soviet Republic of Armenia and founded the “Lusaghbyur” orphanage in Alexandropol. In 1924, Soviet authorities suspend Biørn’s activity. The orphanage was closed, and 33 students were transferred to American Middle East Relief Orphanage. Biørn tries to reconsider the decision, and in 27 August 1924, she addresses a letter to the Commissioner of Public Enlightenment:

“I can assure you that in our institution I have not acted in any way in contrary to the rules and laws of the country. If I have tried to inspire moral principles in the orphans I have gathered, they have not contradicted the great principles you profess… for many years I have been dedicated to the sacred cause of alleviating the Armenian suffering in Turkey, and the case I started in Alekpol two years ago is so close to my heart that I cannot believe that it can be stopped suddenly… I warmly ask you to be kind enough to reconsider your decision about our orphanage and give me the opportunity to continue our work” (11). Of course, no opportunity was given. Biørn moves to Syria and works with the Armenian deportees during 1926-1935. After completing her mission, she returns to Oslo and lives with Fridtjof and her grandchildren. Until her death in 1960, she did not stop talking about the Armenian Genocide. Photographs taken by her, her diary, and many other documents are valuable sources for studying the Armenian Genocide, which are kept in the funds of the "The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute" foundation.

*The submissions were presented to AGMI by Jussi Fleming Biorn, grandson of Bodil Biorn.

Regina Galustyan

AGMI applicant, researcher

1. For more details about the organization see; Matthias Bjørnlund,

“Harput-Missionaries, Danish Missionaries in the Kharpert Province: A Brief Introduction,” http://www.houshamadyan.org/mapottomanempire/vilayetofmamuratulazizharput/harputkaza/religion/missionaries.html. Seen in 23.01.2021.

2. Inger Marie Okkenhaug,

“Spiritual Reformation and Engagement with the World: Scandinavian Mission, Humanitarianism, and Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1905-1914, ” in Christian Missions and Humanitarianism in the Middle East, 1850-1950: Ideologies, Rhetoric, and Practices, eds. Okkenhaug I. M. and Summerer K. S. (Brill, 2020,) 99.

3. The same place, 92.

4. The same place, 100.

5. Alma Johansson, A People in Exil, One Year in the Life of Armenians (Yerevan, Armenian genocide Museum-Institute, 2008), 23, 24, 26.

6. Inger Marie Okkenhaug,

“Scandinavian Missionaries, Gender and Armenian Refugees during World War I. Crisis and Reshaping of Vocation,” Social Sciences and Missions 23 (2010), 74.

7. The same place, 81.

8. The Holy Bible, Ararat translation, Psalm 69, http://www.bible-links.org/. Seen in 23.01.2021:

9. Okkenhaug,

“Scandinavian Missionaries, ” 77, 84.

10. Okkenhaug,

“Scandinavian Missionaries, ” 79.

11. Letter from Head of the Alexandropol Orphanage Bodil Biørn, WMW, to the Public Enlightenment Commissioner, f. 113, l. 38, w. 45, file 191.

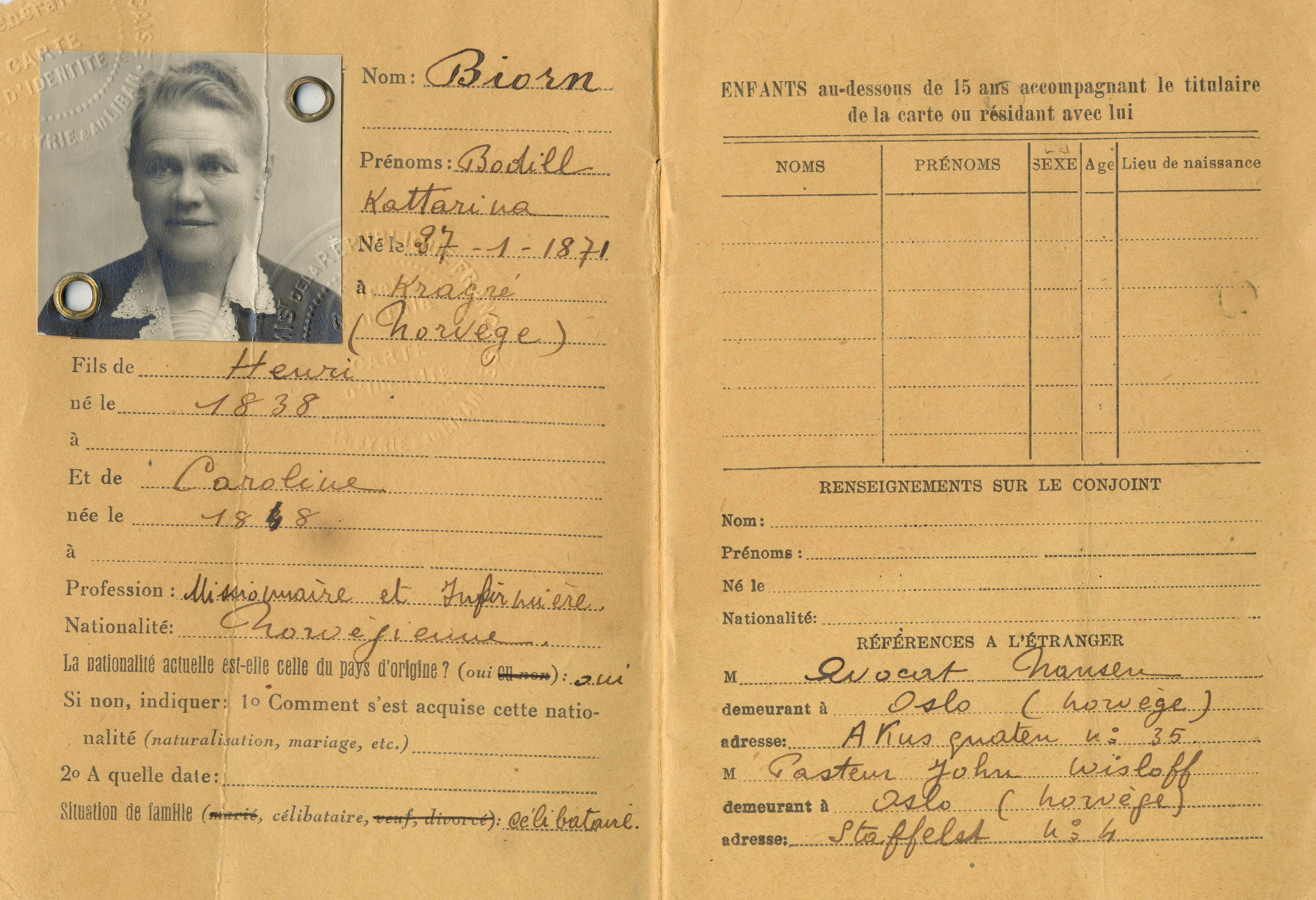

Passport issued to Biørn by the High Commissioner for the French Mandate in Lebanon, 1932

Passport issued to Biørn by the High Commissioner for the French Mandate in Lebanon, 1932

Bodil Biørn nominal fund, AGMI Collection

Fridtjof - Raphael Biørn, postcard

Fridtjof - Raphael Biørn, postcard

Bodil Biørn nominal fund, AGMI Collection

Syringe; from Bodil Biørn’s collection of medical instruments

Syringe; from Bodil Biørn’s collection of medical instruments

Bodil Biørn nominal fund, AGMI Collection