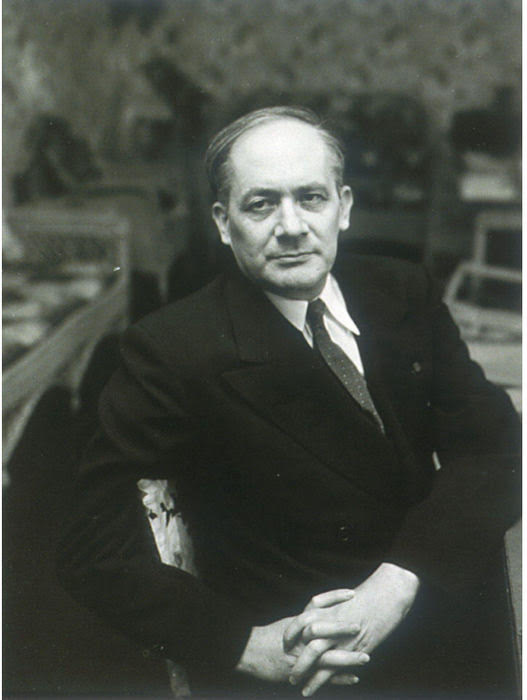

June 24 marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of the prominent human rights activist and lawyer Rafael Lemkin, who made a great contribution to the development and definition of genocide as a separate science. It is noteworthy that the study of the issue of the Armenian Genocide has a special place in the latter’s enormous scientific heritage.

Raphael Lemkin was born on 24 June 1900 in Bezwodne, a village near Volkovyssky that was in the Russian Empire at that time. That is where Lemkin spent his childhood and adolescence, being interested in stories of mass murders.

In his autobiography, Lemkin wrote that he apparently came across the concept of mass atrocities while, at the age of 12, he was reading

Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz, often questioning his mother about such events, in particular the passage describing how Nero threw Christians to the lions and wondering how the emperor could have provided pleasure for the audience in such a way.

The episode worried young Raphael, who immersed himself in reading and devoted himself to the study of the destruction of ethnic groups. Lemkin was fascinated by the subject of atrocities and would often question his mother about events such as the sack of Carthage, Mongol invasions and conquests and the persecution of Huguenots.

Another case that shocked Lemkin were the Jewish pogroms. 70 Jews were killed and 90 were seriously injured in the massacre in the Bialystok region of Poland (then part of tsarist Russia) in 1906.

The next episode that impressed Lemkin was the massacre of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. In this connection, he wrote in his autobiography that more than 1,200,000 people in Turkey had been sentenced to death for no apparent reason other than because they were Christians.

It is noteworthy that the impressions of the massacre of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire remained in his memory. When he was 21 years old and a student at the University of Lvov, he was informed by a local newspaper of the assassination of the former Ottoman Interior Minister Talaat Pasha by Soghomon Tehlirian in Berlin. Lemkin began to follow Tehlirian’s trial.

On this occasion, he wrote in his autobiography:

“One day I read in the newspapers that all the Turkish criminals were to be released. I was shocked. A nation is killed, and the perpetrators have been set free. Why is one person punished when he kills another, while killing millions is a lesser crime? Turkish criminals released from Malta have spread around the world. The most horrible of them was Talaat Pasha, the Turkish Interior Minister, who is identified with the annihilation of the Armenian people. Talaat Pasha took refuge in Berlin. One day a young Armenian named Tehlirian stopped him on the street. After recognizing Talaat Pasha, he shot him. Tehlirian’s trial actually became that of a Turkish criminal.

The fact that Turkish criminals who committed the Armenian Genocide remained unpunished was a matter of concern for Lemkin; he drew the attention of his professor of criminal law to the question of why Armenians did not arrest Talaat for the massacres. The professor replied that there was no law under which he could be arrested.

“Consider the case of a farmer who owns a flock of chickens”, said the professor, “he kills them, that’s his job; if you intervene, you are harassing him.” Lemkin responded:

“Armenians are not chickens.” The professor tried to substantiate his argument:

“When you interfere in the internal affairs of a country, you are violating that country’s sovereignty.”

“Is it a crime for Tehlirian to kill a man, but killing more than a million people for a dictator is not considered to be one?” Lemkin asked. He then said,

“This is a most contradictory thing.” Lemkin was surprised that the “flag of sovereignty” could protect people trying to destroy an entire minority. Wasn’t it possible to create a norm in international law that worked for the prosecution of mass murder?

This question led Lemkin to change his field of study: from linguistics to the study of international law. In later years, when he was already teaching at Yale Law School, he used to tell his students how Tehlirian’s trial had changed his life.

Lemkin’s additional interest in the peculiarities of the history of the Armenians and the massacres they suffered was also due to the fact that, when he was studying at the University of Lviv, there was a vibrant Armenian community there. Professors of Armenian descent were lecturing there, and many of Lemkin’s classmates were of Armenian descent.

In an interview with CBS in 1949, Raphael Lemkin said:

“I became interested in genocide because it has happened so many times; it happened to the Armenians, who were treated very harshly at the Versailles Peace Conference because the criminals guilty of committing their genocide were not punished”. Then, referring to the revenge by the Armenians and the murder of Talaat Pasha, Lemkin said the following:

“They (the Armenians) created a terrorist organization that took justice into its own hands. The assassination of Talaat Pasha in Berlin is very instructive. A man (Soghomon Tehlirian), whose mother was killed during the genocide, killed Talaat Pasha... As a lawyer, I thought that a crime should not be punished by its victims, but by a court under international law.”

Lemkin studied law for six years, first in Lviv and then at Heidelberg University. He was disappointed by the fact that he couldn’t find legal norms to ban the killing of racial and religious groups anywhere. While working as a prosecutor in Warsaw in 1929, he began to draft an international law that would oblige the governments of sovereign states to stop the targeted destruction of ethnic, national, and religious groups. It was this draft law that Lemkin introduced to his European colleagues (law specialists) during the 5th International Conference on Criminal Law in Madrid in 1933.

Lemkin defined the crime of "barbarism" as an act committed against human life with the intention of destroying a certain national, religious or social group and the crime of "vandalism," as the destruction of works of art and culture. Lemkin's proposals presented at the Madrid conference in 1933 were, however, ignored by the international community.

On 24 August 1941, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Winston Churchill addressed the people on the radio. He called the genocide committed by the Nazis an “anonymous crime.” Churchill’s statement changed Lemkin’s approach, and he aimed to write a book describing how the Nazis used the law to justify the regular extermination of Jews and other European minorities. Lemkin intended to create a new term to describe the killing of national, religious and racial groups.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace published, in November 1944, a paper entitled “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe,” in which Lemkin argued that the proposals he put forward in 1933 constituted, in fact, the concept of genocide.

“By “genocide” we mean the destruction of a nation or an ethnic group. This new word is derived from the Greek word genos (race, tribe) and Latin word cide (kill). Lemkin, a lawyer and linguist, tried to shock the audience with the short and terrifying term "genocide" that would have much greater impact than the previous term “crimes of vandalism and barbarism,” used in his book.

In April 1945, on the eve of Germany’s defeat in the war, the victorious countries of World War II agreed on the basic principles of the trial of war criminals.

Lemkin joined the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal and became a legal adviser to U.S. Attorney-General Jackson. The lawyer hoped that the concept of "genocide" would be included in the indictment against the main war criminals. His success was not complete, although the term was used in the indictment and in the final arguments during the trial, but “genocide” was not recognized as a separate crime.

After the Nuremberg Trials Lemkin focused on creating an international document condemning genocide, to be presented at the UN General Assembly. On 11 December 1946, Genocide Resolution 95(1) was adopted by the UN General Assembly, which meant that the extermination of human racial, religious, national and linguistic groups was declared to be a crime under international law. UN Secretary-General Trigge Lee then asked Lemkin to draft a genocide convention. The development of this project was carried out by Lemkin, French lawyer Donnedieu de Vabre, and the Romanian legal expert Vespasian Pella in April-May 1947.

Lemkin and his colleagues presented a “Secretariat draft” (UN document E/447), as the first draft of the Genocide Convention on June 26, 1947. The “Secretariat draft” was amended by an ad hoc commission of the UN Economic and Social Council, which represented sovereign states.

The revised draft was finally presented to the UN General Assembly in September-December 1948. The text of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948. The main purpose of this convention was to confirm that genocide is a crime under international law. The intention to destroy certain groups was particularly important in the definition of the crime, as Lemkin stated that both the cases of Armenian Genocide and the Jews’ Holocaust were based on the intention to exterminate Armenians and Jews as separate groups.

Lemkin’s concern over the condemnation of the Armenian Genocide led him to set a clear goal for Turkey to be one of the first countries to ratify the convention. Lemkin stressed the need to accept the Convention in order to exclude the possibility of leaving criminals unpunished, as demonstrated by the example of the Armenian Genocide. According to him, the lack of such a convention was the reason why Turkish criminals managed to escape punishment and the young Armenian avengers punished them.

It should be noted that Raphael Lemkin left a great number of documents, much correspondence, numerous articles, manuscripts and photographs, etc. After his death, these collections were donated to various archives. Lemkin’s masterpiece, which could have been the main achievement of his life, was a history of genocide.

Lemkin and his student assistants were already working on a book on the history of genocide in the 1940s. Information has been preserved shows that he was even preparing to publish a four-volume study of the subject in 1956. The first volume was to be devoted to the theory of genocide and the other three would discuss 62 historical cases of genocide in the ancient period, the Middle Ages and in the modern era. Chapter 39 of the third volume was to have been about the Armenian Genocide. But he did not manage to complete this work.

The large volume of various materials related to the Armenian Genocide preserved in Lemkin’s collection proves that he had given a lot of time and thought to the study of factual materials related to it. The denialists, however, did not ignore Raphael Lemkin and his scientific legacy. Moreover, an attempt has been made to falsify the exclusive significance of the Armenian Genocide in Lemkin’s works. Despite this, the facts about Lemkin's activities play an important role in neutralizing denial theses on various platforms.

Narek M. Poghosyan

PhD in History, researcher at the Comparative Genocide Studies Department at the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute Foundation.

International lawyer Raphael Lemkin helped draft the Genocide Convention, which maps out prevention and punishment for the crime of genocide.

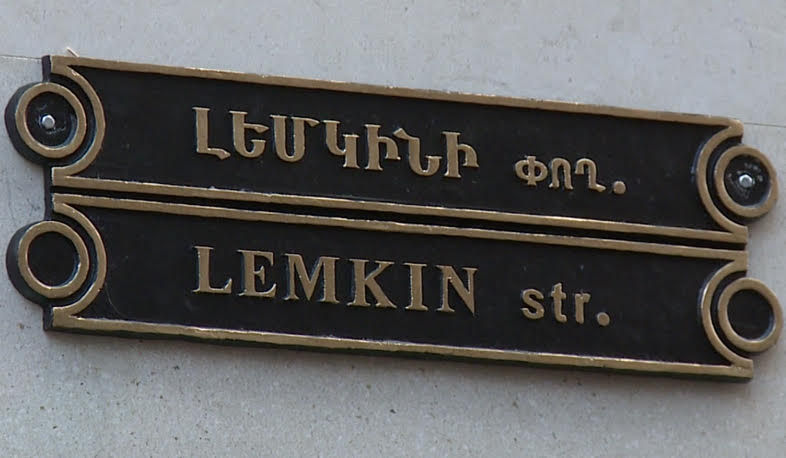

Լեմկինի փողոցի ցուցանակը Երևանում։

Հայաստանը Նիդեռլանդներից հետո աշխարհի երկրորդ երկիրն է, որտեղ Լեմկինի անվան փողոց կա։

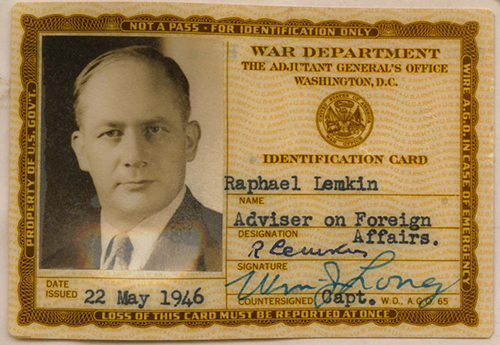

Պատերազմական վարչության նույնականացման քարտ, 1946 թ. մայիսի 22

Ռաֆայել Լեմկինի հավաքածու

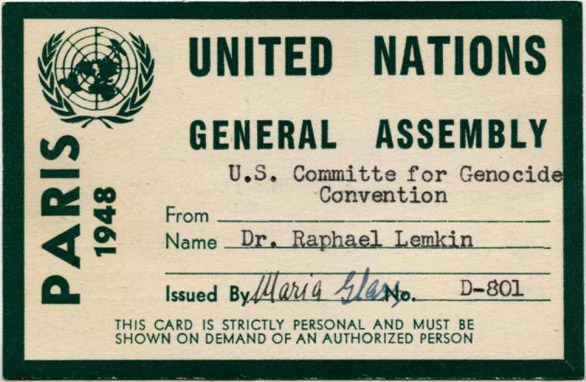

Միավորված ազգերի կազմակերպության Գլխավոր վեհաժողովի նույնականացման քարտ, 1948 թ.

Ռաֆայել Լեմկինի հավաքածու