31.07.2021

Grandmother Vardanush with her son Patvakan’s family

The great tragedy of the Armenian Genocide realised by Turkey’s sinister hand that began in April 1915 did not leave any Armenian family uninvolved. My recent ancestors also became its victims, suffering the consequences of those tragic events.

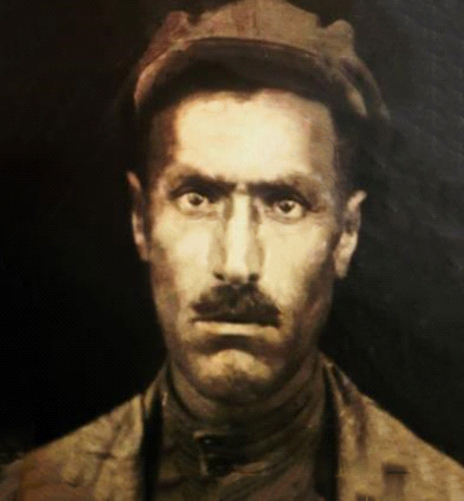

My great-grandfather, the married priest Rev. Petros, was a well-known, respected and wealthy clergyman in the village of Gharavank in Kaghzvan province. His father’s name was Grigor. About 500 Armenians lived in Gharavank before World War I. My grandfather Samson, a son of Grigor's family, was alas, never seen by any of his grandchildren. My father was named Vardevan (Vardan) and was Samson Petrosyan’s son. My grandfather's family bore the surname Ter-Petrosyan being from a clergyman’s family, but later part of the name, the "Ter" was dropped, probably after they emigrated to Soviet Armenia.

Rev. Petros had seven sons and would proudly announce everywhere that his family had given seven soldiers to the homeland. He never had daughters. Unfortunately, I only know the names of six of Rev. Petros’ seven sons: Ishkhan, Patvakan, Aghabab, Vardevan, Minas and Samson. I suppose Rev. Petros' seventh son would have been named after his father, Grigor.

When I was little, I always wondered where my grandmother Vardanush found three of her sons’ unusual names - Vardevan, Patvakan and Aghabab. But when I grew up and my grandmother, father and uncles told me my grandfather Samson's family history, I realized that my uncles’ names were not randomly chosen, but the response to an old and sad story.

The story that I’ll set down was related to his wife, my grandmother Vardanush, by my grandfather Samson. She, in her turn, passed it down to her sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren.

This is the story that my grandfather Samson told my grandmother.

Turkish police arrested the young Armenians and threw them in jail. My grandfather was among them. Every day, reading their names and surnames, individuals were called out and killed. One day grandfather Samson's name was read out. The Turkish commander ordered one of the policemen to

"Cut off that gyavur's (infidel’s) head, dip his clothes in blood and return them to him." The Turkish policeman took my grandfather to a deserted place to kill him.

Samson bowed and put some soil into his mouth as a sign of Christian confession and blessing before he died. At that moment, his wide back seemed to be very familiar to the Turk. He asked my grandfather where he was from, and when he learnt that he was Samson, son of Rev. Petros from Kaghzvan, he dropped his gun and hugged him. It turned out that the askyar (soldier) had served in the Samsons' house in Gharavank years before and that Samson's father had saved his family from starvation. He reminded my grandfather that he was Ali and that he had carried him on his shoulders until he was ten years old. My grandfather remembered him. Ali waited until it got dark, then took Samson to his home, killed a calf, soaked his clothes in its blood and took them to his commander.

Ali's son was dead, but his young daughter-in-law lived in his house. Samson told my grandmother that the woman was indescribably beautiful and that Ali always tried to persuade him to marry his daughter-in-law and become his son. But Samson always refused. When Ali tried to persuade him one last time, my grandfather Samson had the courage to say,

“If you want to, you can kill me here, but I will not marry a Turkish woman and I will not become a Turk.”

Ali finally realised that it was pointless to try to persuade young Samson and helped him pass over the border one night; my grandfather thus returned to his native village, Kaghzvan. However, only its ruins remained. The Turkish invasion of 1918 had wiped out almost everything. Seeing the door to his paternal house locked, Samson suddenly remembered his father's command to his children: "If you ever return home from a distant place and see the door closed, go and dig under our walnut tree. If our family's wealth is buried there, then we have fled and left our village." Samson dug under the walnut tree, and when he saw the jar of gold, he cried bitterly and reburied it, hoping that one day everyone would return home.

Then the Armenian-Turkish war began. The Kemalist army began shelling the village at night and there was no other way but to take the road to exile. Samson wandered for a long time and eventually reached Etchmiadzin. At that time, all the refugees arrived in Etchmiadzin, taking refuge under the sacred walls of the mother monastery. Etchmiadzin was full of refugees and orphans. Samson unexpectedly met his uncle Minas among them and spent the nights in various places with him, half-starved. Hunger and his nephew’s poor state forced Minas to persuade Samson to leave Etchmiadzin, go to a village and look for work or a place to live, hoping that they would soon return via Kars, to their native village of Kaghzvan.

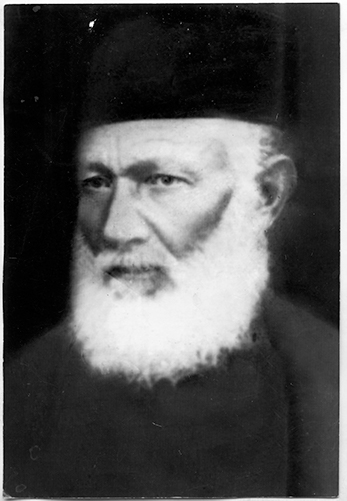

Samson reached the village of Kosh (ancient Kvashavan, which was a fief belonging to the Arsacid dynasty). A Kosh resident, Vanush Gevorgyan, whom we call uncle Vanush, told me that when he came to Kosh, my grandfather met their relative Abraham, whom the local people called Apo. He hired young Samson to work in his home. One cold winter day, Vanush's grandmother, Lusntag, saw Samson crying in the street. Asked why he was crying, Samson replied that even a dog lived a better life than he did. He told her about the carefree and luxurious life he had lived in his father's house; they had servants, and now he was homeless and hungry, suffering for a piece of bread day and night, in the cold and storms. Grandmother Lusntag, deeply moved, asked and persuaded her husband to have Samson live with them. Her husband knew that Apo would not give Samson to him, so he turned to the priest. Together they persuaded Abraham to release him. Samson moved to Rev. Gevorg’s house. Seeing Samson's humanity, diligence, intelligence and literacy, Father Gevorg loved the boy very much and adopted him in the village church as the fourth (adopted) brother to his sons Khachatur, Vachagan and Benjamin. Samson becomes a member of family and supported Rev. Gevorg’s sons.

Rev. Gevorg, after some time, decided to get Samson married. The family quickly constructed a small house for him and he was married to a refugee family’s daughter Vardanush. Seeing, during the wedding, that the people from Sasun drank a lot, my grandfather said to someone, in Russian, that these people were mad and that, if they drank, there would, inevitably, be a fight. One of the people from Sasun heard this and told his relatives. Later, when they were taking the bride to Kosh village, the guests from Sasun, armed with rifles, stopped Samson and members of Rev. Gevorg’s family. They insisted that they return with the girl. Despite the pleas made by Rev. Gevorg, they refused to give way. In desperation Rev. Gevorg promised to give them several animals, so they would allow him to take the bride to her new home. He later fulfilled that promise.

After his marriage Samson had four sons, whom he named after his brothers and father: Petros, Ishkhan, Vardevan, Patvakan and Aghabab. Petros and Ishkhan died of starvation when they were still children. Later, my father, Vardevan, named his firstborn child after my grandfather Samson, and my uncle Patvakan named two of his three sons after his missing uncles, Ishkhan and Petros. They say my brother Samson was like my grandfather, not only in appearance but also in intelligence and literacy. My grandfather Samson was very literate. He learnt several languages during those years.

Samson Petrosyan died of scurvy at a young age in 1935. He was buried in the cemetery next to St. Gevorg Church in the village of Kosh, which later became his family’s resting place. His grave is above that of his spiritual father, Father Gevorg. To this day, when talking about my grandfather in the village of Kosh, they call him Samson of Pzan. Pzan is Father Gevorg’s family name. Everyone in the family loved my grandfather very much and their children and grandchildren did not know until recently that Samson was not their real uncle.

After Samson's death, his aunt Eva found my father and my uncles. Eva was a living witness of the Armenian massacres of 1915. She kept some of her gold in a narrow piece of cloth around her waist, using it to reach Armenia with only four of her ten children by bribing Turkish askyars (soldiers). Six of her children and her husband had been killed by Turkish askyars (soldiers) on the road to deportation. Unfortunately, I am not aware of the hardships she, a single woman with four surviving children, had suffered before they arrived in Armenia.

Eva originally lived in Alexandropol (now Gyumri). There was an epidemic there in during those years and aunt Eva was hospitalised. When she returned, she could not find her four children whom she had left to the grace of God. Some told her that her sons had died, while others said that the Americans had taken them to America with other orphans.

Eva lived in the village of Kosh for some time. The natives always remembered Eva riding a horse, wearing trousers and guarding the vineyards of the village. They say that Eva was famous as a “manly woman” in the village because of her strong nature.

Aunt Eva Zadoyan lived with uncle Patvakan’s family in Yerevan until the end of her life and never found her sons. She prayed for her children for an hour every morning and evening and did not share her pain with anyone.

We heard, from less reliable sources, that my grandfather Samson's father, Rev. Petros, lived in Yerevan all that time, but they never met. What a bitter fate!

Many years later, when my uncle Samson's son, Aghabab, was working as a construction foreman in Jrvezh, demolishing old houses to build new ones, an old man told him angrily, “Wherever we went, our houses were demolished, what kind of life is this?”

“Which house of yours was demolished, father?”

“My house in Kaghzvan, my son,” replied the old man.

My uncle found out that the old man knew my grandfather's father, Rev. Petros. Aghabab told his brothers this. My uncle Patvakan found out that my grandfather Samson's brother's son-in-law, Vardevan, lived in Etchmiadzin and met him there.

Vardanush’s family story

My grandmother Vardanush's family also has a tragic history. Her family emigrated from Erzrum in 1915. Her father and uncles had been very rich and famous people there. My grandmother's father's family members managed to escape from Erzrum, while her uncle’s young son hid the family valuables from the Turks but wasn’t able to escape.

Later local people, who migrated to Armenia, said that the Turks captured him and having beaten him, forced him to tell them where their family wealth was hidden, promising to release him. He showed them a large pit in the courtyard of their house in which he had hidden his family's gold, precious items and carpets. The Turks, breaking their promise, killed him and took all grandmother Vardanush's family’s wealth.

I am very sorry and always reproach myself that even though we have our own TV studio, Ashtarak TV, I never filmed my grandmother. Everything I’ve related she could have told in detail as a living witness of the Armenian Genocide of 1915; about her and my grandfather Samson’s life, about their migration…

Author and narrator: Gayane Petrosyan, Samson and Vardanush Petrosyan’s granddaughter

Edited by Armenian Genocide Victims Documentation and Data Collection Department

Grandfather Samson

Rev. Gevorg

Aunt Eva with her nephew Patvakan’s family