News |

ZABEL YESAYAN. FOR THE SAKE OF THE ARMENIAN ORPHANS

Zabel Yesayan

Zabel Yesayan

catastrophe offers thousands of orphans up to your love and care. When you hear their names,

do not think of them the way one thinks of the victims of a remote, obscure tragedy.

Try, rather, to see your own child in all of them; mourn each and every one individually;

and open your hearts wide, open them without reserve to this unlooked-for, this grief-stricken motherhood.

One of the most prominent Armenian writers who witnessed and narrated the Armenian atrocities, Zabel Yesayan was a publicist, literary critic, public figure and had a great role in the salvation of the Armenian orphans. She went to Cilicia after the Adana massacres of 1909 as a member of the Patriarchate’s second delegation which had the aim of gathering up Armenian orphans and founding an orphanage. Three months later, having partially fulfilled her mission, Yesayan returned to the capital of the Empire in September, 1909. She published her book “In the Ruins” in Constantinople in 1911. This was a “report” of her activities in connection with the Adana massacres and its consequences.

Yesayan was the only woman on the list of the Armenian intellectuals targeted for arrest on April, 1915. She was able to evade arrest and flee to the Caucasus, where she worked with refugees and orphans, documenting their eyewitness accounts of atrocities. She spoke about the persecutions against Western Armenians in Baku and Tiflis then travelled to Petrograd and Moscow, where she organized fundraising for Armenian orphans and refugees. She was involved in Armenian refugee and orphan issues in Middle Eastern countries in 1918. By her own wish, and in accordance with the decision of the Armenian National Delegation, she was sent to Cilicia to regulate the work in the orphanages there. Zabel Yesayan was appointed a director of the Adana Orphanage, but in June 1920, after transferring the Orphanage to the French Administration, she resigned from her position. She was then involved in the organization of the evacuation of Armenian orphans from Cilicia and began her collaboration with the Armenian delegation at Paris peace conference led by Avetis Aharonyan.

In 1922 she was already in Paris where she continued her literary activity and published her books “My Soul in Exile” and “Hours of Solitude.”

Regian Galustyan

AGMI applicant, researcher

* Before reaching Mersin, while we were still en route, we learned that orphans from Adana had found shelter in Smyrna’s German orphanage. When we arrived in Smyrna, an anguishing, nervous impatience impelled me to go see those twenty-six orphans. It was our first encounter with any of the victims.

The orphanage’s director, a thin, gray-haired woman with an aristocratic face, told us at great length about the widowed mother’s despair, the depression some were suffering from, and the reluctance of almost all of them to give up their children. “As soon as I learned of the events in Adana, I felt it was my duty to be there. I set out immediately with a young Armenian woman who was orphaned during the 1895 events and is now one of my best assistants…Our mission was a hard one and put severe demands on us. Try to imagine it. Adana was a hell. On the still smoldering ashes, mothers in their death agony, wounded or crippled mothers, would entrust their children to us so that they could die with an easy conscience. Often they regretted it immediately afterward…They would call out after us that we had torn their child from their arms and, fixing indignant, aggrieved eyes on us, would beg us to give them back their baby. We had to adapt to their changing moods with untiring patience.’’

“The children who remained with us were those who had lost their parents and had been found roaming wounded and half-naked in the ruins. Sometimes even those little refugees, those vagrant, terror-stricken orphans, would be reunited with their mothers. Those women, their faces smeared with blood and grime, their ayes blind with weeping, and often wounded as well, would somehow manage to find their way to us and reclaim their children. Sometimes they would insult or threaten us. They had the strength of a lioness in their words and gestures. A couple days later, the very same woman, faint with hunger and drained by physical suffering, would bring us their children again and turn them back over to us. This time, they would leave without uttering a word.’’

** “Ma…Mama!’’

Groping, hesitant hands, agonized hands, clung to us or grabbed at our hair. In a supreme, blissful illusion, eyes belonging to eight-year-old or perhaps ten-year-old children flew open - eyes made prematurely old by suffering, black, woebegone eyes. They stared at us for a moment, astonished, and then, suddenly understanding that we were outsiders, closed again, resentful and sad, shutting us out.

One can comfort young people, women, the old. One can offer wretches at death’s door a glimmer of hope and happiness. But what could we do to alleviate the abiding grief that made those little children unreceptive and self-absorbed?

With heavy hearts and embittered souls, we wandered from bed to bed. Every time we took note of the information recorded about a child, it was: “Father – killed. Mother – killed, or blinded, or, perhaps, crippled.” Like an apparition, a ghastly, crimson image from the days of the catastrophe flashed before our eyes.

__________________________________________________________

Zabel Yessayan, In the Ruins: the 1909 Massacres of Armenians in Adana, Turkey, (Boston, Massachusetts: Aiwa Press, 2016).

|

|

DONATE |

TO KEEP THE MEMORY OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE ALIVE

Special Projects Implemented by the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute Foundation

|

COPYRIGHT |

|

AGMI BOOKSTORE |

The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute’s “World of Books”

|

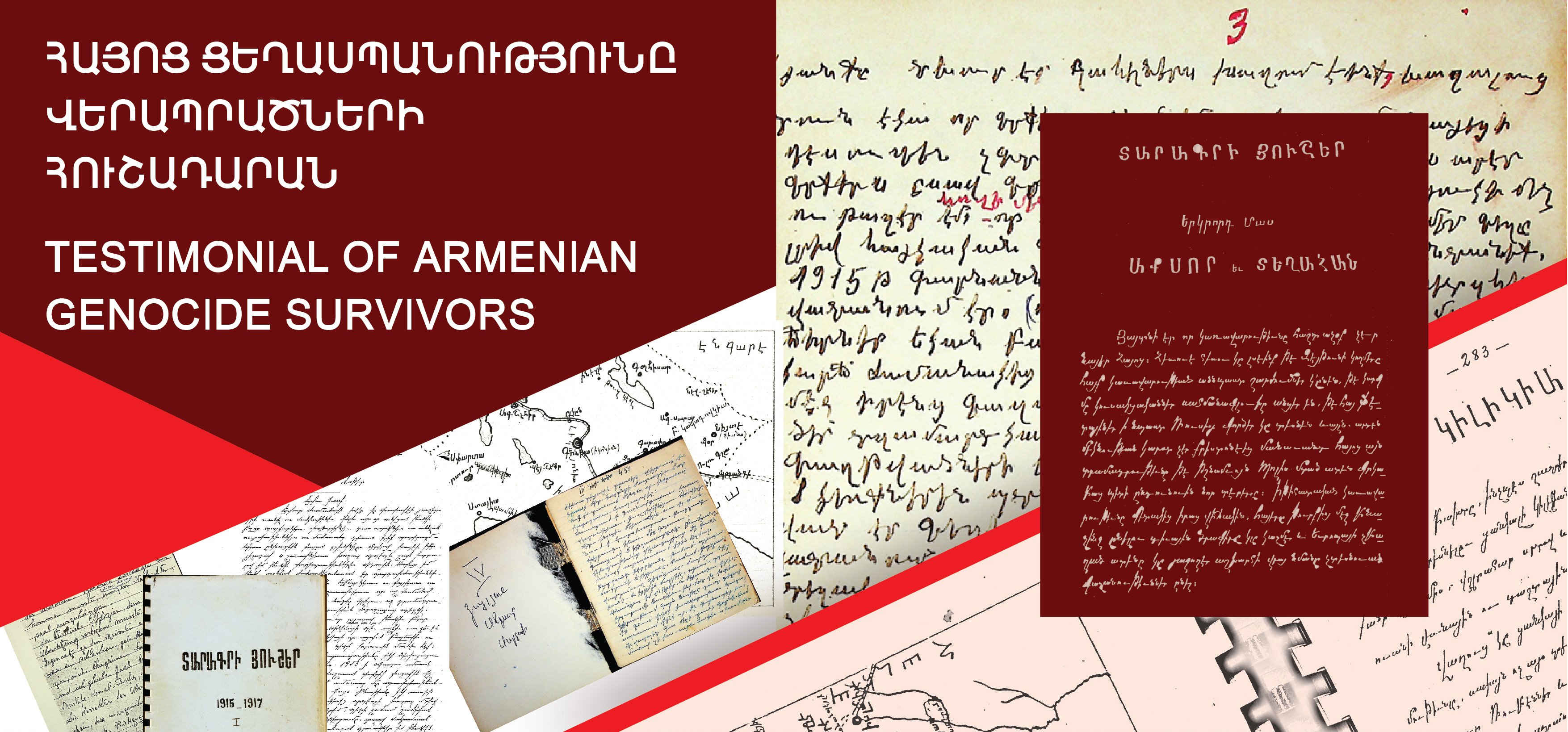

TESTIMONIAL OF ARMENIAN GENOCIDE SURVIVORS |

THE AGMI COLLECTION OF UNPUBLISHED MEMOIRS

|

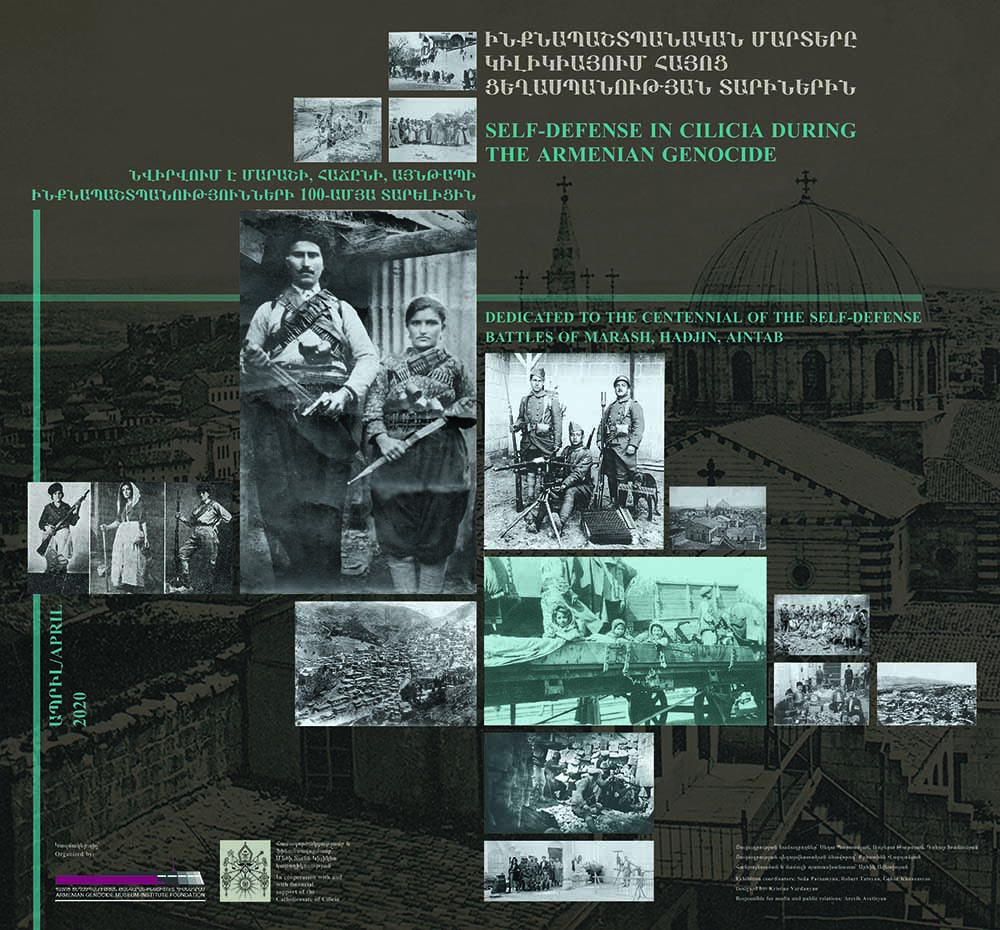

ONLINE EXHIBITION |

SELF-DEFENSE IN CILICIA DURING THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE

DEDICATED TO THE CENTENNIAL OF THE SELF-DEFENSE BATTLES OF MARASH, HADJIN, AINTAB

|

LEMKIN SCHOLARSHIP |

AGMI ANNOUNCES 2024

LEMKIN SCHOLARSHIP FOR FOREIGN STUDENTS

|

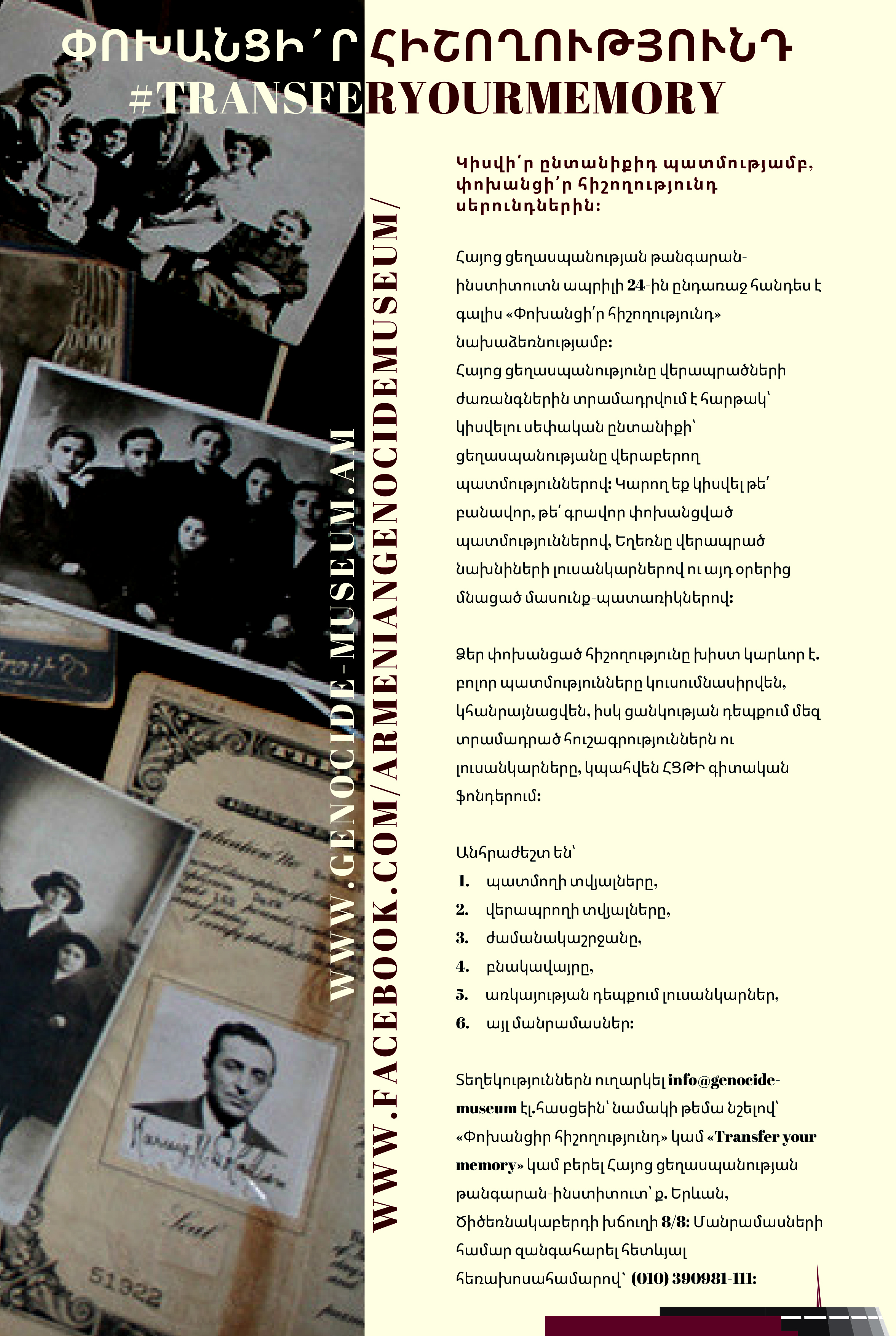

TRANSFER YOUR MEMORY |

Share your family story,

Transfer your memory to generations.

On the eve of April 24, the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute undertakes an initiative “transfer your memory”.

|

|