Survivors stories |

Varter Bogigian-Nazarian’s story

village of Hussenig, Kharpert

By Hagop Martin Deranian

Varter was born in 1885 in the lively village of Hussenig which, with its population of five thousand, was located in a valley a few miles below the flourishing and more urban city of Kharpert.

It began with the ominous knock on the door in the middle of the night. The Turkish gendarmes said that they wished to make some immediate purchases in the Nazarian store. Mugrditch was not given time to dress but left his tranquil home dressed only in pajamas.

Varter never saw her husband again. No one agreed on the precise fate of Mugrditch Nazarian. Some say he was taken out of town a few miles and shot. Others relate that he was among those who were imprisoned in Mezireh and exposed to inhuman tortures so unbearable that he and the other prisoners poured the kerosene from the jail lamps onto themselves and ended their lives as human pyres.

A few days later, on June 11, the horror began for Varter, all the more frightening since she was nearly full term with another child. Ordered to prepare for “deportation”, she gathered her infirm in-laws, her maid Tamam, and her children, Eghisapet, Takouhi, Nazareth, Yeghsa, Arakel and Avedis.

She obtained a donkey with a saddle bag with two pockets. In each pocket she placed one of her smallest children. The next day, the gendarmes pushed the donkey with its two children down a mountainside and to their deaths.

“I saw Varter at noon”, a fellow companion tearfully recalled of that day, “and when I saw her again in the evening, I could not recognize her, She was almost naked”. “Elmas”, Varter said to her friend in utter anguish and pain, “let us find a well and throw ourselves into it”. At that moment of despair, some Arab woman took pity on her and drew some water from the well and quickly gave it to her before the gendarmes saw. They had been traveling in these terrible conditions for a month and a half since leaving Mezireh.

One morning soon thereafter, Varter awoke with her children and saw that the caravan had moved on. Seizing the opportunity to hide, she descended into a dry well with her children. There she remained safely for two days without food. A passing Arab, some say a Pasha, came to the well and shouted into it, “If there is anyone down there, let him speak, as I am about to throw stones in the well”. “No, don't throw any stones”, Varter shouted, “I am here with my children”. “Very well” the Arab replied, “I will help you out”. Varter was relieved. “Help my children out one at a time”, she pleaded. “Then I will come”. “No!” the Arab emphatically responded. “You come first so that we may pull the children out together”. Hesitatingly and very slowly, Varter lifted herself out. Seeing her comeliness, the Arab seized her and forcibly adducted her. He was totally deaf to her appeals for her children left in the well. Their echoing voices cried after her, “Mother, Mother!” Those infant cries haunted and tormented her the remaining days and dark nights of her life. The dry hole became Varter’s wailing well.

M.Teranyan, Husseinik. Memories and Emotions about Native Hearth and People, Boston, 1981, pp.180-189 (arm)

|

|

DONATE |

TO KEEP THE MEMORY OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE ALIVE

Special Projects Implemented by the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute Foundation

|

COPYRIGHT |

|

AGMI BOOKSTORE |

The Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute’s “World of Books”

|

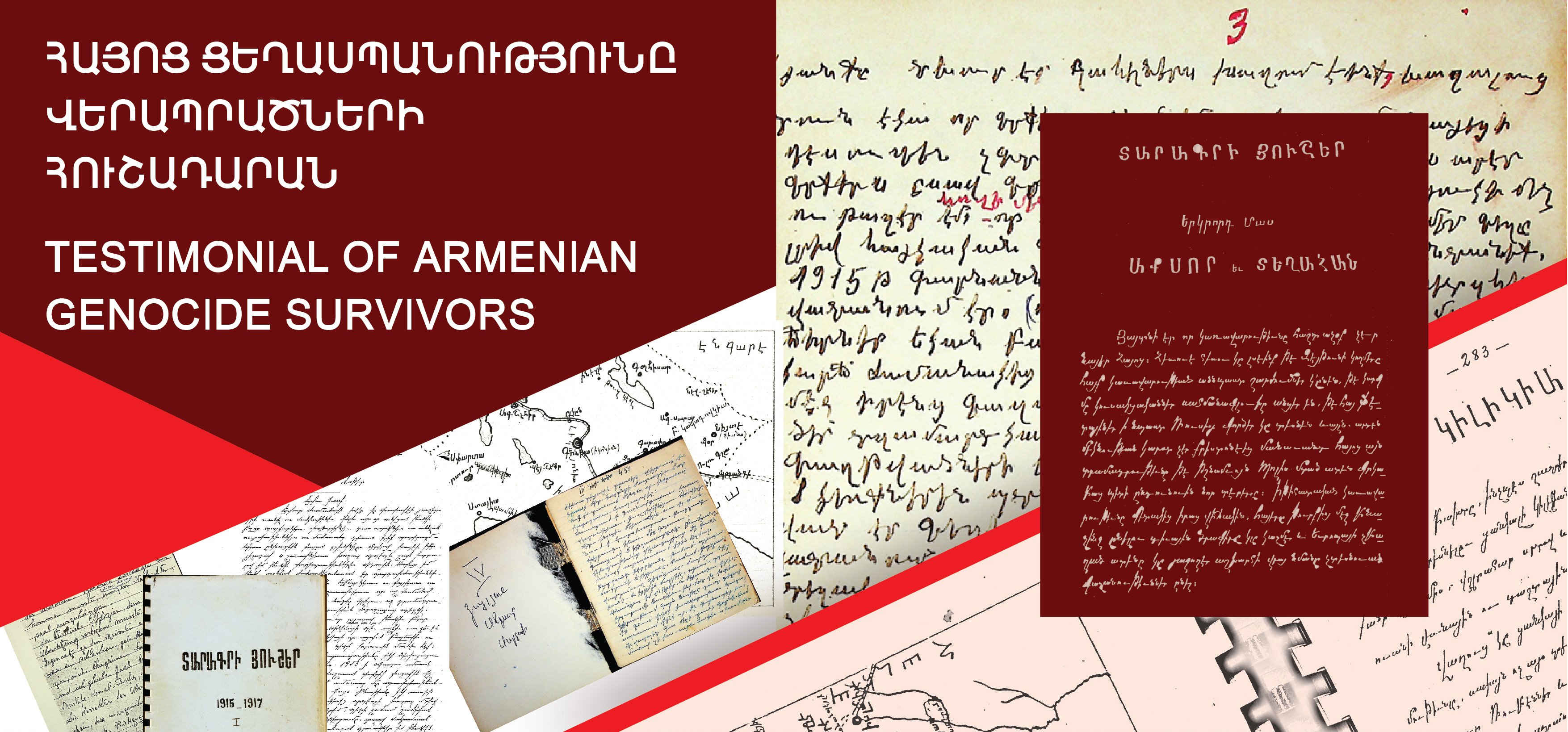

TESTIMONIAL OF ARMENIAN GENOCIDE SURVIVORS |

THE AGMI COLLECTION OF UNPUBLISHED MEMOIRS

|

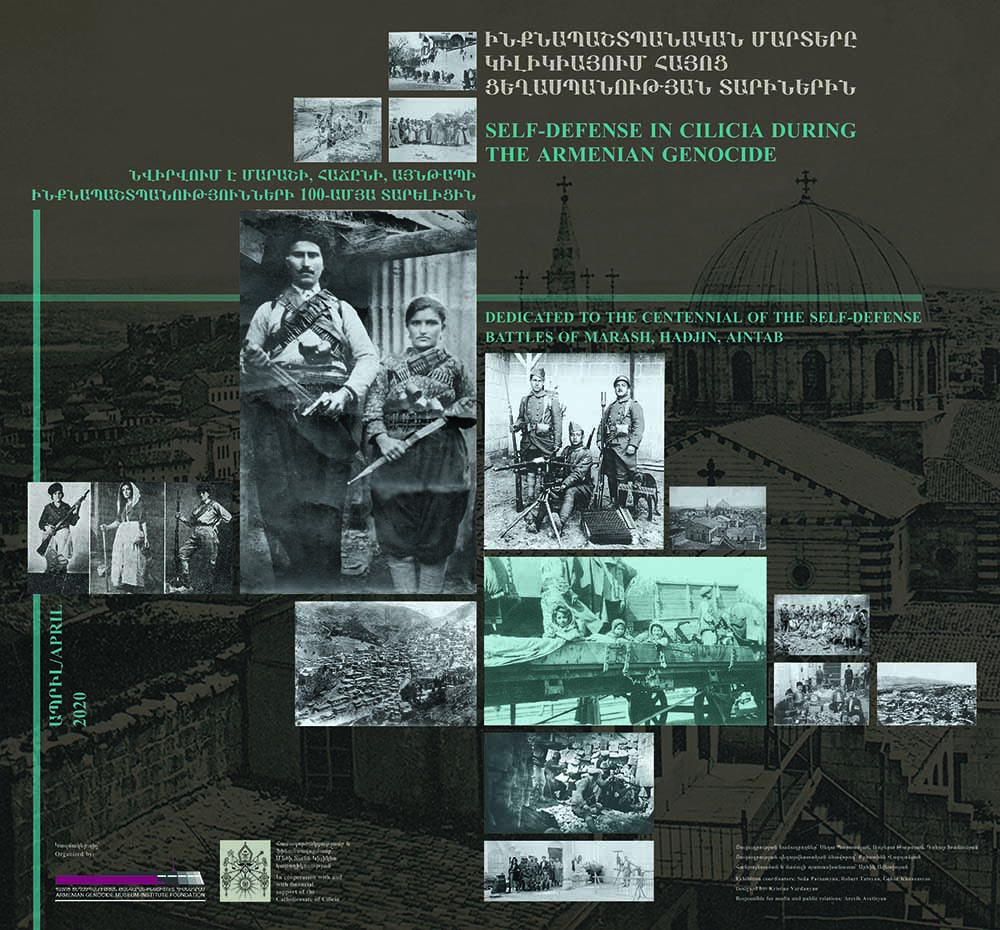

ONLINE EXHIBITION |

SELF-DEFENSE IN CILICIA DURING THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE

DEDICATED TO THE CENTENNIAL OF THE SELF-DEFENSE BATTLES OF MARASH, HADJIN, AINTAB

|

LEMKIN SCHOLARSHIP |

AGMI ANNOUNCES 2024

LEMKIN SCHOLARSHIP FOR FOREIGN STUDENTS

|

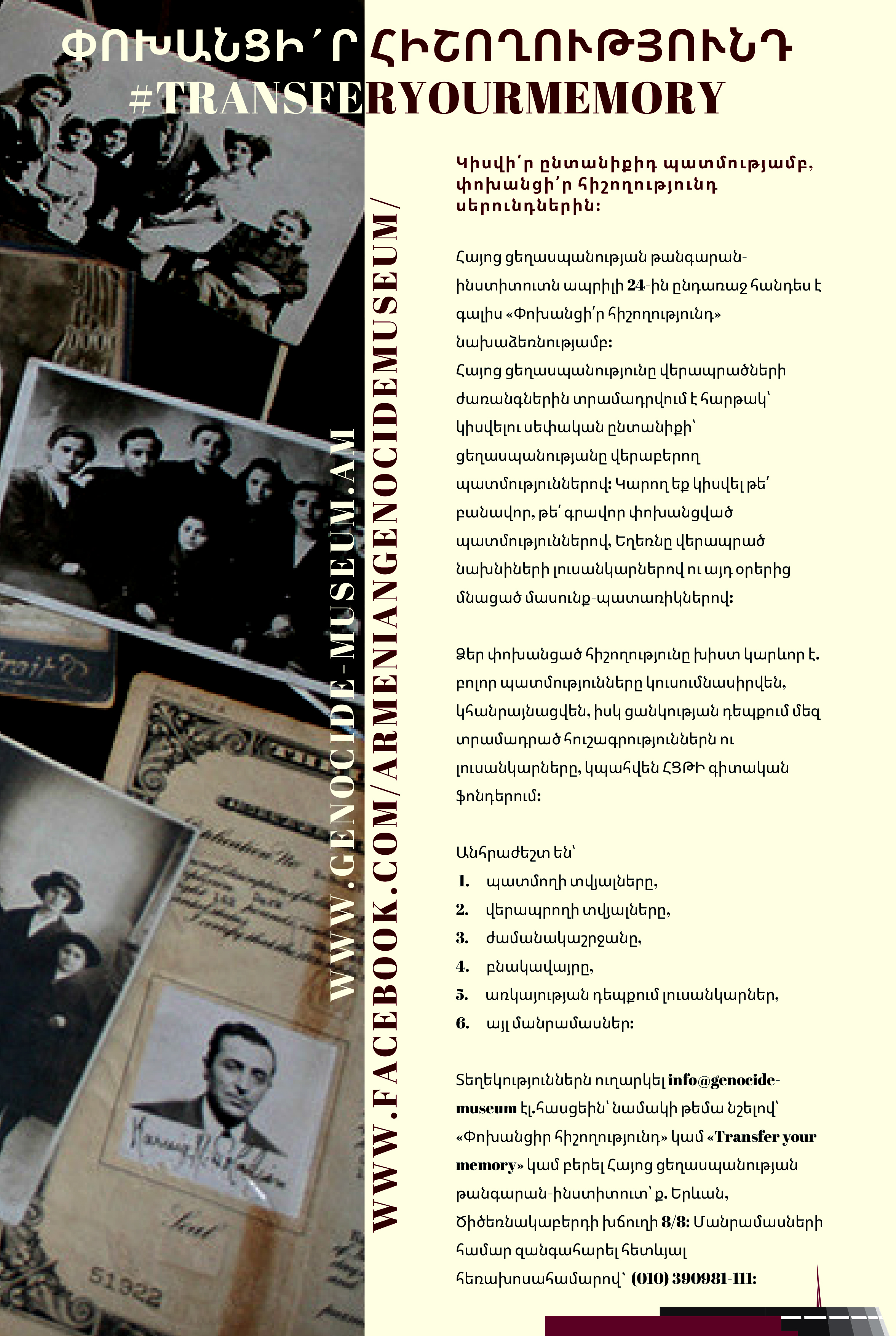

TRANSFER YOUR MEMORY |

Share your family story,

Transfer your memory to generations.

On the eve of April 24, the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute undertakes an initiative “transfer your memory”.

|

|